3 Core Spatial Concepts

The following core spatial concepts are considered assumptions in most spatial analysis methods. They provide a useful framework for thinking about how geographic data works and how spatial relationships are modeled in GIS.

In many cases, these assumptions hold up. However, practicing critical GIS also means we should interrogate these assumptions. When are they not true? How do they shape the output of our analysis? For each of the following concepts, consider when they might not hold up. Understanding these moments of mismatch helps us become more thoughtful and responsible spatial analysts.

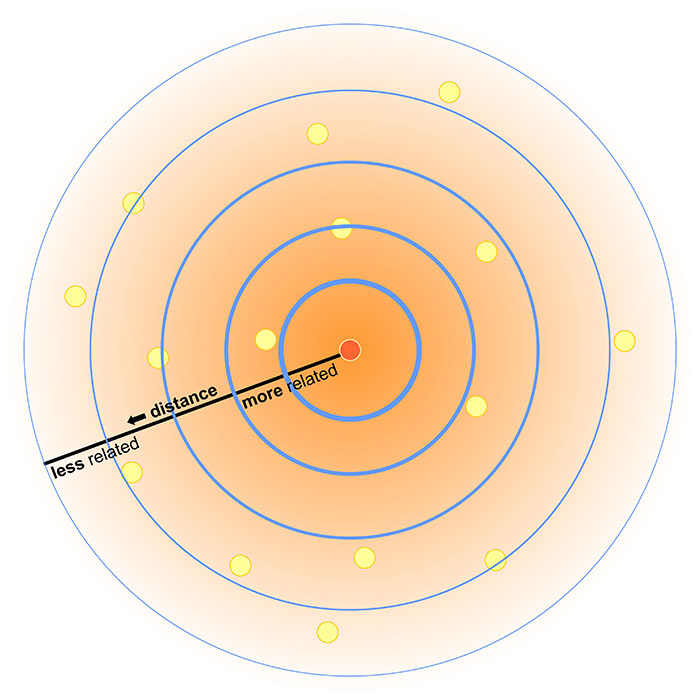

3.1 Tobler’s First Law of Geography

This “law”, coined by geographer Waldo Tobler in 1970, states that “everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things.” This principle captures a foundational idea in spatial analysis: spatial relationships tend to weaken with distance. As a result, places that are closer together tend to have stronger influence on one another than those farther apart. This assumption underlies most geographic models and spatial analysis methods. For example, consider the spread of an infectious disease like the flu. When the flu begins spreading in a city, nearby neighborhoods would tend to see more outbreaks than distant areas. This pattern occurs because people are more likely to come into contact with others in close proximity.

3.2 Distance decay

Distance decay is the concept that underpins Tobler’s First Law of Geography. Distance decay describes the tendency for interaction between two things to decrease as the distance between them increases. This pattern is driven by the friction of distance (the idea that distance imposes a cost) whether in time, money, or effort, which in turn reduces the likelihood of interaction. For example, consider how you choose a grocery store. If two stores are similar in price and quality, you are more likely to visit the one that is closer, because it costs less time and fuel to reach. However, this example also highlights that friction of distance can be modified. You might willingly travel farther to visit a store that has a product that you can’t get at your local store, which illustrates that the strength of distance decay depends on context and motivation.

3.3 Spatial autocorrelation

Spatial autocorrelation describes the degree to which values observed at nearby locations are similar (positive autocorrelation) or dissimilar (negative autocorrelation). It reflects the principle that spatial data are not independent- nearby places often share similar characteristics. For example, it is more likely for adjacent neighborhoods to have similar home prices than two neighborhoods on the opposite sides of town. Ignoring spatial autocorrelation can lead to biased or misleading results in statistical analysis because standard models assume independence between observations.

3.4 Scale

Scale refers to the spatial or temporal level at which data are collected or mapped. Cartographic scale refers to the relationship between distance on the ground and distance on the map. A small-scale map covers a larger geographic area and a large-scale map covers a smaller geographic area. This confusing terminology is due to the fact that this is defined based on the representative fraction, which represents the ratio of a map unit to a unit on earth (for instance 1in:5000ft vs 1in:500ft). Spatial scale refers to the size of the geographic unit (for example, analyzing neighborhoods vs. states) and the spatial extent of the analysis. Read why spatial scale is important here

3.5 Modifiable Areal Unit Problem

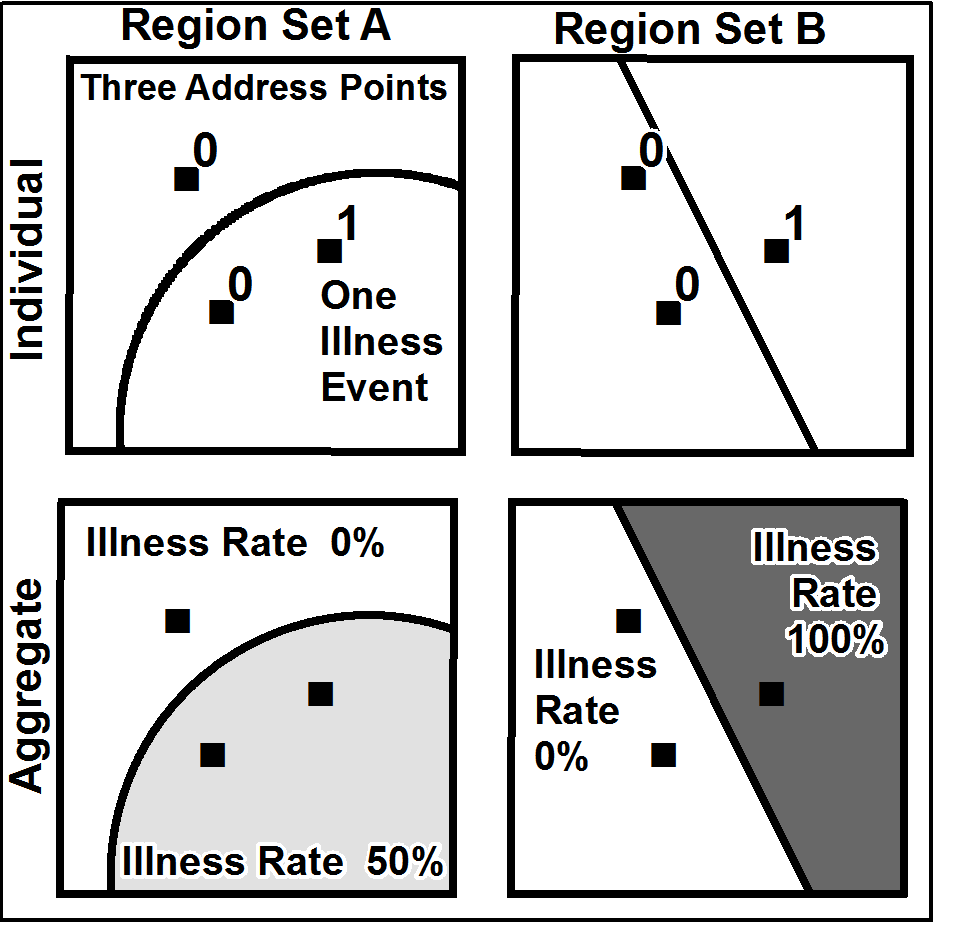

The Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP) refers to the bias that can occur when point-based/individual level data are aggregated into spatial units like zip codes, census tracts, or counties. The patterns and results of a spatial analysis can change significantly depending on how the boundaries are drawn (zoning effect) and how large or small the units are (scale effect).

For example, calculating the average income of a population using census tracts may yield different patterns than calculating the same average using counties even if both are using the same underlying household-level data (scale effect). A common example of the zone effect is redistricting, where voting districts are redrawn, often in response to population changes, but where different ways of grouping the same population can significantly alter political outcomes.

Consider the summary statistics for percent poverty across North Carolina zip codes vs. counties to see the impact of the scale effect:

| Aggregation Unit | Mean | Median | Min | Max | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zip Code | 25.22 | 23.76 | 0 | 100 | 13.82 |

| County | 226.46 | 25.48 | 12.34 | 40.83 | 6.58 |

The MAUP matters because most spatial data analysis relies on aggregated units, which are often arbitrarily or administratively defined, not necessarily aligned with meaningful social, environmental, or economic boundaries.

3.6 Spatial hierarchies

Spatial hierarchies refer to the idea that we can often organize geographies within nested levels. For instance, city blocks within a neighborhood within a city within a state. These hierarchies often shape how spatial processes operate across space/scale- some phenomena are localized, while others operate at broader scales.

3.7 Ecological fallacy

The ecological fallacy occurs when analyses draw conclusions about individuals based on aggregate data for a group or area. For instance, knowing that a neighborhood has a high unemployment rate does not mean everyone who lives there is unemployed.

3.8 Edge effects

Edge effects refer to the distortions or inaccuracies that occur at the boundaries of a study area. When a study region is artificially cut off, important relationships or influences from outside the boundary may be ignored, leading to misleading conclusions. For example, a pollution study limited to county borders may miss the upstream source of a contaminant. Edge effects are particularly problematic in environmental, ecological, and neighborhood analyses, where spatial context beyond the border often matters.

3.9 Spatial non-stationarity

Spatial non-stationarity means that the relationship between variables changes over space. For example, the relationship between income and education may be strong in one North Carolina county and weak in another. Traditional statistical methods assume consistent relationships, but since spatial data often violate this assumption there are techniques like Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) that are designed to explore spatial non-stationarity by allowing coefficients to vary across space.

3.10 Location, place, and territory

Location refers to the position of something on the Earth’s surface, either in absolute terms (e.g., coordinates) or relative to other features (e.g., “north of here”). Place goes beyond location to include the meanings, experiences, and emotional attachments people associate with a space. Territory refers to a bounded area that is claimed, governed, controlled, or contested.