1 Introduction

This text is a primer on geographic thinking and spatial data, designed for GEOG370: Introduction to Geographic Information at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. It blends foundational concepts in Geographic Information Science with opportunities to apply geographic concepts using QGIS, an open-source Geographic Information System software.

1.1 How did we get here?

Humans, as a species, have always had to orient ourselves to our environment and use our brains and bodies to move through and interpret space. We have always “thought spatially” about where things are, why they are there, and what it means that those things are there. Our spatial ability is a major part of our cognition, and the ability to navigate and analyze space has allowed us to evolve as a species. As our societies became more complex and our social networks grew, so did our need to externalize spatial knowledge. This process of externalizing spatial knowledge, or making our understanding of space visible and communicable, has taken many forms over time. Today, a major way that we externalize spatial knowledge is by collecting, analyzing, and sharing spatial data. This course focuses on geographic information: how knowledge about space is created, represented, and stored. It also explores Geographic Information Systems (GIS), the most common tool used today to analyze and visualize that information.

Over time, a dominant, institutionalized way of externalizing and analyzing space emerged: Cartesian spatial logic. This is the idea that space can be abstracted into something measurable, gridded, uniform, and detached from lived experience. This logic became foundational for activities like statebuilding, infrastructure planning, and population management—projects that benefit from standardizing and controlling space. As a result, many of the systems we use to collect, organize, and analyze geographic data today are rooted in this way of thinking. These systems are not neutral; they reflect particular assumptions about how space should be known and used.

Other ways of understanding and representing space have always existed. This course will ask students to critically interrogate the assumptions built into dominant forms of spatial representation and analysis. What kinds of spatial knowledge are emphasized, and what gets left out? How are data, analysis, and outputs shaped by political, social, and historical forces?

1.2 Asking spatial questions

A spatial question is concerned about the role of space in influencing how our world works. For instance:

- Are there a disproportionate number of landfills in minority communities?

- Which streams are most at risk from polluting facilities?

- Where is the best place to locate new affordable housing in Carrboro?

- Who lives within 10 minutes of their nearest hospital?

- Which parts of Chapel Hill have the most well-connected sidewalks?

- Where are urban tree canopies most and least dense?

- Which intersections have the highest number of pedestrian accidents?

- Where are the highest-performing schools located, and who lives near them?

- What areas show high levels of commercial vacancy?

- How has land use changed in downtown Durham since 1950?

- Where are population densities increasing most rapidly within North Carolina?

Spatial questions can ask about (from Nyerges (1991)):

- Location

- Where is it?

- Why is it here or there?

- How much of it is here or there?

- Distribution

- Is it distributed locally or globally?

- Is it spatially clustered or dispersed?

- Where are the boundaries?

- Association

- What else is near it?

- What else occurs with it?

- What is absent in its presence?

- Interaction

- Is it linked to something else?

- What is the nature of this association?

- How much interaction occurs between the locations?

- Change

- Has it always been here?

- How has it changed over time and space?

- What causes its diffusion or contraction?

Answering spatial questions requires analyzing geographic data- information that is tied to a location on Earth’s surface. This data can come in many forms (e.g. satellite imagery, census records, land use maps, environmental sensor data, GPS data), many of which will be explored in this class.

1.3 What is a Geographic Information System?

One common method for exploring spatial questions (using geographic data) is a Geographic Information System (GIS). A GIS is an integrated framework for exploring spatial questions. It is built around combining hardware, software, data, people, and methodologies to analyze space. In this course, we’ll use GIS as a tool to help us examine geographic data, but the focus is not on learning GIS software in depth. Rather, we’ll use it to support broader learning about geographic information and spatial thinking.

| Component | Description |

| Hardware | Physical infrastructure used for GIS. This includes local computers, servers, data collection devices, etc. |

| Software | Applications and platforms used to analyze, visualize, and manage geographic data. |

| Data | Data suitable for analysis in a GIS requires a locational component |

| People | Users, developers, analysts, and decision-makers who interact with GIS. |

| Methodologies | Techniques that are implemented inside a GIS to process data and answer spatial questions. |

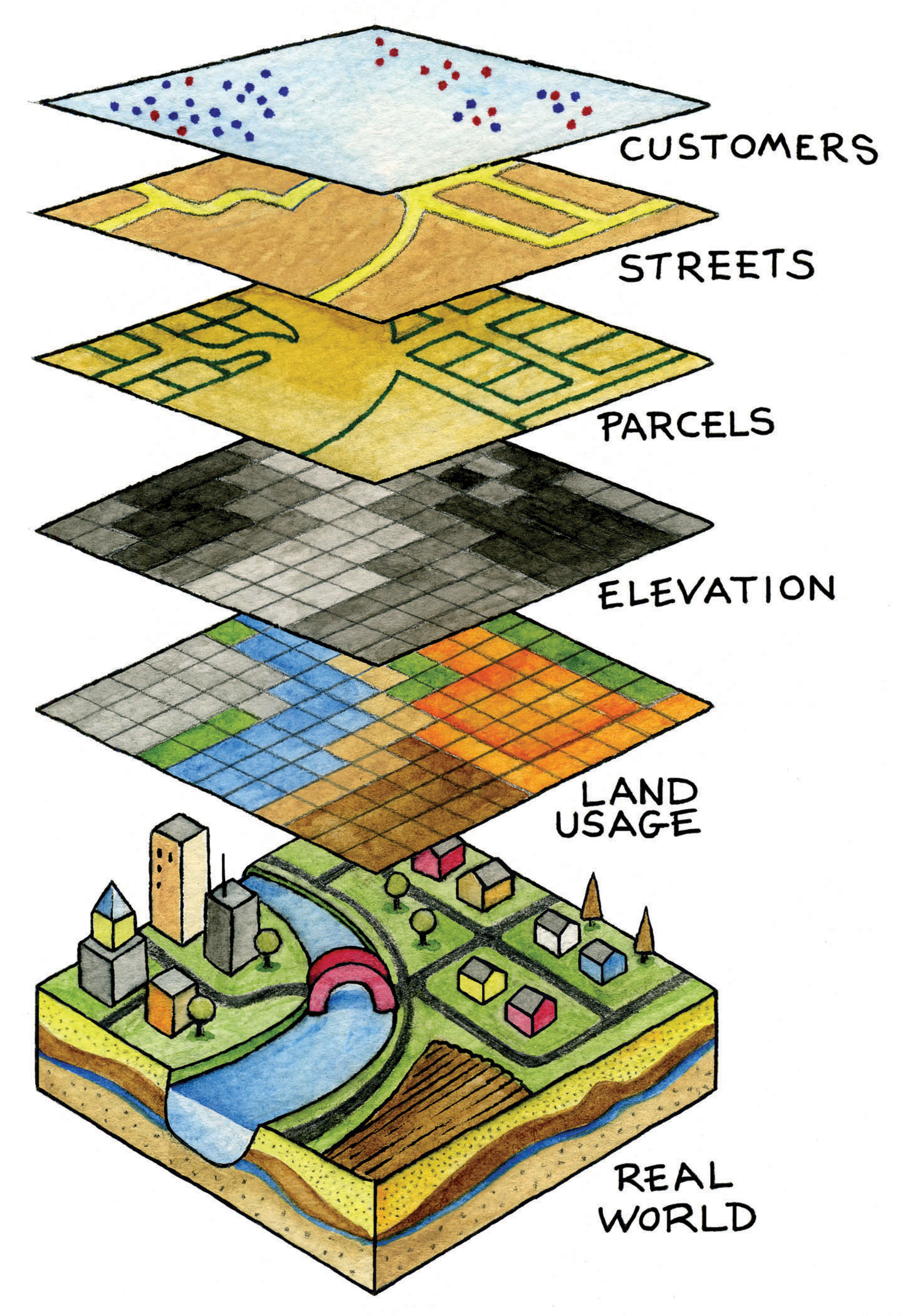

1.4 The Layer Model

In a GIS, spatial features are thought of as a set of layers. In the layer model, the world can be represented by translating real-world phenomena into a model composed of separate, stackable layers. For instance, a layer model representing the ecology of North Carolina might have a layer representing rivers, one representing forests, and one representing species ranges.

The layer approach necessarily relies on abstraction: the process of simplifying complex real-world features into layer representations that GIS software can manage and analyze. Trying to represent every feature with complete accuracy is impossible from a data storage, collection, and analysis perspective

Abstraction always involves decisions, and those decisions will impact the outcome of any GIS analysis using the data. Abstraction is guided by the original purpose of the dataset. The purpose allows data creators to determine what aspects of the real-life feature are important (and therefore should be collected and represented with high accuracy) and which aspects are less important (and can be generalized or omitted). A mismatch between your purpose for using the data and the abstraction decisions made in the data creation process can be a serious issue for the reliability of your results.

Consider the following example of different uses for the same dataset- hospitals in North Carolina:

- An engineer assessing flood risk at hospitals in North Carolina

- A public health analyst investigating disease outbreaks across hospitals in North Carolina

What is considered important to these two users differ greatly. The engineer may require detailed building footprints to evaluate structural exposure. The public health analyst may want detailed information on the number of beds and the infectious disease protocols, but just need a rough location for the hospital. If these users were creating the datasets themselves, they would likely look very different. However, most of the time, users aren’t collecting or creating the data themselves, they’re working with data that already exists. As a result, it’s crucial for users to critically evaluate the dataset’s underlying abstraction decisions regarding:

- Selection - What features are included or excluded?

- Classification - How are features grouped?

- Simplification - How much detail of the original feature is retained?

- Resolution- What is the smallest feature the data can meaningfully represent?

Furthermore, all spatial data comes with some degree of uncertainty and error

- Errors include positional inaccuracies, attribute inaccuracies, or conceptual inaccuracies

- Uncertainty refers more broadly to the limits of our knowledge about the data. This might include incomplete data, ambiguous classifications, unknown data sources, or the inability to verify how a measurement was taken.

What ultimately matters is not whether the data is perfect, but whether the level and type of abstraction, error, and uncertainty are acceptable enough for the analysis you are doing.

1.5 Limits of the Layer Model

The layer model depends on a Cartesian spatial logic, which is a framework that treats space as something that can be quantified, segmented, and rationalized. In Cartesian logic, space is imagined as fixed (every location has a precise, mappable set of coordinates), abstract (detached from the meanings people assign to it), homogeneous (space is uniform), and measurable (can be divided into distances, areas, and directions). This standardized view of space underlies many of the spatial practices GIS draws from- spatial analysis, cartography, land surveying, remote sensing, and military mapping.

But this model has limits. The idea that space can be broken into layers, each objectively representing a part of the world, leaves out other ways people understand and interact with their environments. Spatial logic is not universal. Different cultures and communities experience space in ways that are relational, embodied, and emotional. What matters in a landscape may not be what’s easily mapped, and what’s included in a GIS layer may not reflect how people actually move through or value a place.

To that end, there are many alternative conceptualizations of space. For instance:

Doreen Massey (Massey (2005))

- Space is relational

- Formed through interactions, from the global scale to everyday encounters.

- Space is the sphere of possibility

- Multiple trajectories coexist; space exists because of multiplicity and difference.

- Space is always under construction

- It’s a process- never fixed or finished, made up of “simultaneities of stories-so-far.”

Henri Lefebvre (Lefebvre (1991))

Space is made up of:

- Spatial Practice (Perceived Space)

- Physical and material space as experienced in daily life (e.g., walking through a city).

- Representations of Space (Conceived Space):

- Abstract, planned space created by experts (e.g., maps, zoning, blueprints)

- Spaces of Representation (Lived Space):

- Emotional, symbolic, and cultural space as lived and felt by people.

- Societies privilege conceived space, which fragments and commodifies the world. This abstract space suppresses difference and bodily experience. Through reclaiming space (imagining and enacting alternatives) we can move toward differential space: a space that embraces multiplicity, creativity, and the right to difference.

1.6 What is Critical GIS?

Critical GIS recognizes that GIS is not a neutral tool, it is a power-laden practice. As a subfield or alternative knowledge structure, critical GIS has been employed as a critical analysis of GIS, and as a critical analysis through GIS. A critical analysis of GIS examines the origins, development, and institutional uses of GIS technology, highlighting how it has been shaped by and contributed to systems of power, including those of the state, military, and private industry. This strand interrogates the assumptions embedded in spatial data, software design, and dominant spatial logics. A critical analysis through GIS uses the existing tools and methods of GIS to advance social justice, expose spatial inequalities, and support marginalized communities. This includes work such as mapping environmental racism, visualizing housing insecurity, or enabling participatory planning processes that center community knowledge. Critical analysis through GIS also includes the development of alternative spatial methods, such as feminist GIS, counter-mapping, and qualitative GIS.

Read: O’Sullivan, David. “Geographical information science: critical GIS.” Progress in human geography 30, no. 6 (2006): 783-791.