2 Politics and Potentials of GIS

This chapter introduces GIS not as a neutral technical tool, but as a sociotechnical system. That means GIS is shaped by the social, political, and historical contexts in which it was/is developed and used. We’ll trace the development of GIS across three interrelated domains: as a system of tools (GISystems), as a scientific field (GIScience), and as an object of critique and transformation (critical GIS). Understanding this development will help us think critically through, against, and beyond GIS.

2.1 Historical Foundations

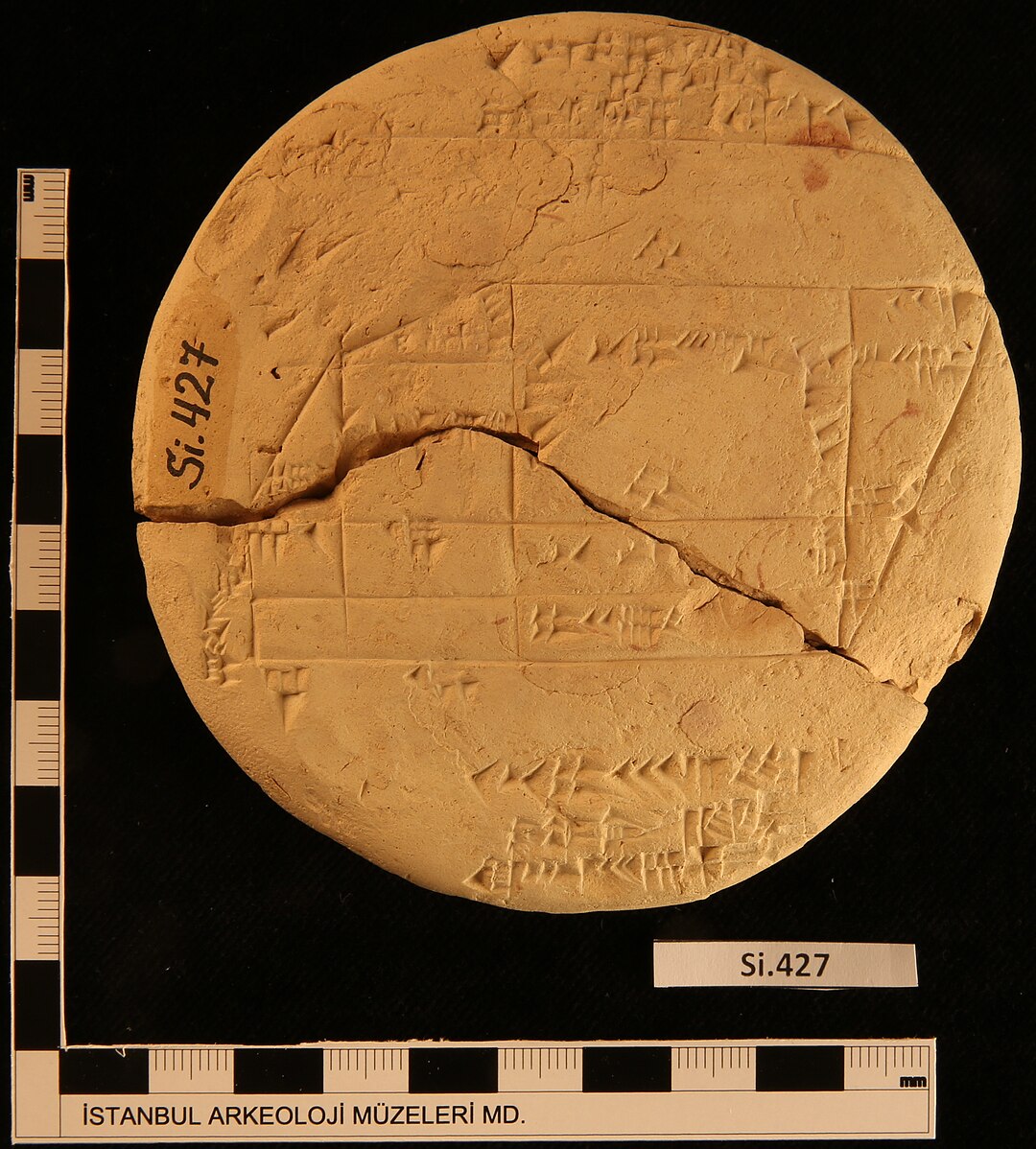

As introduced in Chapter 1, humans have always thought about, analyzed, and represented space. Even in ancient times, people developed systems to record and interpret spatial information and these systems were almost always closely tied to state-building and governance. As early as 1900 BCE, the Babylonians were using advanced applied geometric methods to divide valuable farmland, documenting these divisions on some of the earliest known cadastral maps.

GIS (Geographic Information Systems) has become the main way that we visualize and analyze spatial data. Spatial analyis is concerned with extrating additional insight from spatial features. There are many examples of pre-digital spatial analysis, for instance, John Snow’s 1854 cholera map, which plotted cholera deaths across London and revealed a cluster near a contaminated water pump, ultimately helping to identify the source of the outbreak. However, the widely recognized birthplace of modern GISystems is our northern neighbor. Roger Tomlinson, an employee of the Canadian government, created the first computerized geographic information system. This system, named the Canada Geographic Information System, was designed to store geospatial data for the Canada Land Inventory, allowing analysts to inventory and overlay different datasets (layers) of natural resources in Canada. While the actual mechanics differed significantly from modern GISystems, the underlying logic of layering and analyzing spatial data remains the same today.

2.2 Corporate Dominance

While the Canada Geographic Information System was developed for a specific government use case, it quickly became clear that the logic of GISystems could be applied across virtually every public and private sector. As various government institutions and private industries began to see the potentials of GISystems, it quickly became a valuable (and marketable) product. In the United States, one of the early hubs for GISystems development, particularly broad-use GISystems development, was the Harvard Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis, which was founded in 1965. This lab developed some of the first general-purpose GISystems software tools. While the lab’s priorities were research/academic focused, these academic developments quickly lead to growing commercial interest.

One of the lab assistants in the Harvard lab, Jack Dangermond, went on to found the Environmental Systems Research Institute (Esri), which originally focused on land use planning consulting. Over time, Esri pivoted towards software development and released a series of increasingly dominant GIS tools that created a flexible GISystems framework that could be applied across urban planning, resource management, transportation, environmental monitoring, defense, etc.

Esri’s business success is due to a couple main reasons:

- Esri developed tools with a graphical user interface (GUI), which means that GISystems became much more accessible to non-programmers through point-and-click functionality (as opposed to the command line).

- They introduced file formats like the shapefile and geodatabase, which became de facto standards across the GIS industry

- As organizations invested in Esri’s ecosystem, switching to other systems became prohibitively expensive and time-consuming (vendor lock-in). When the U.S. federal government became an early adopter, this lock-in cascaded down to state and local governments, contractors, and educational institutions.

- Because of this vendor lock-in, Esri developed what Joe Morrison terms “pedagogical capture”. Because Esri became the industry standard, universities trained students in Esri software; and because students entered the workforce already trained in Esri, employers demanded continued use of Esri products.

By the early 2000s Esri products were essentially synonymous with GISystems software (think Kleenex). Despite the existence of alternatives, GISystems education and practice became deeply embedded in Esri’s proprietary ecosystem, shaping how people learned to think about and use geographic technologies. Today, Esri maintains a dominant market share across sectors, even as open-source and code based (especially R and Python) alternatives emerge. While these alternatives challenge Esri’s monopoly in important ways, Esri remains a powerful force in shaping not just the tools we use, but the assumptions, practices, and institutions that define GISystems. Alongside the rise of corporate GISystems has been the rise of what I think of as the “inevitability” of GISystems. The idea that of course this is how we manage and analyze space and spatial data.

2.3 The Emergence of Critical GIS

As the utilization of GISystems increased in the late 20th century, some academic researchers began to argue that it was more than just a technology, it was the foundation for a new scientific field. Scholars like Dobson (1983) and Goodchild (1992). were the leaders in defining Geographic Information Science (GIScience) as the study of how geographic data is created, analyzed, and understood. They saw GIScience as a way to make the field of geography more rigorous, predictive, and unified through shared computational methods. GIScience focused on formalizing geographic techniques for modeling, storing data, and executing spatial analysis and focused especially on how these approaches can be integrated into a GISystem. The GIScience field also aimed to address core challenges in analyzing spatial data, like how to represent space and time, how to deal with uncertainty and error, how scale affects analysis, and how spatial thinking could be formalized in algorithms.

At the same time, other scholars began to explore and critique the epistemological assumptions embedded in GIS (Systems and Science). Epistemology is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. It asks questions like:

- What counts as knowledge?

- How do we know what we know?

- What are the limits of knowledge?

- What makes something true?

The assumptions in GIS are rooted in positivism, which is the idea that knowledge comes from direct observation and measurement, and that scientific methods can lead us to discovering objective truths about the world. In a positivist view, GIS is seen as a neutral, technical tool for producing accurate representations of spatial reality (which is exactly what the GISciencers were arguing). This view of GIS considers that:

- The world is made up of discrete, observable spatial objects

- Space is absolute, continuous, and measurable

- Knowledge is produced through empirical data and computational logic

- Mapping and visualization produce objective truths

- Problems can be solved through technical optimization

- Data is neutral and meaning arises from analysis, not context

- The GIS user is a rational decision-maker

Scholars such as Sheppard (1995) began to argue that GIS is not a neutral system, it is a social technology. This means that GIS is shaped by the social, political, and institutional context in which it was developed (Cloud (2002)).

Pickles (1995), a recently retired processor in our department, critiqued GIS for reinforcing a positivist, technocratic view of space at a time when human geography was moving away from an emphasis on formal spatial models and towards a more critical, interpretive, and qualitative approach for analyzing space. This thread of academic work developed “strong critiques of the reductionist ontology of spatialism”, in which space can be fully understood through a neutral lens. Instead, he argued that space is socially and politically constructed.

Building on these critiques, scholars working in critical GIS began to argue that GIS is not just shaped by power, it also produces power Specifically, the data and methods used in GIS reflect specific values and assumptions. GIS often privileges quantitative, state-collected, or market-driven forms of knowledge, while excluding local, Indigenous, or experiential understandings of space. Its methods rely heavily on technical models that assume space is continuous, measurable, and comparable, even when that doesn’t reflect how people live and move through the world. Critical GIS raises concerns about how these assumptions and practices have supported surveillance, marginalized alternative spatial perspectives, and reinforced top-down ways of organizing and knowing space.

The increasing gulf between the enthusiasts and the critics of GIS culminated in a meeting at Friday Harbor in Washington State in 1993. The Friday Harbor meetings are widely recognized as the beginning of the formalization of critical GIS, which became known as the GIS and Society research agenda. Rather than deepening the rift between critical geographers and GISciencers, the Friday Harbor conversations were focused on “finding a way to talk across” epistemological divides and explore what GIS might become (Crampton and Wilson (2015)). This meeting encouraged a shift “from critique to involvement,” inviting geographers to ask not just whether GIS was compatible with critical theory, but how it could be used critically (Crampton and Wilson (2015)).

In the years that followed, a range of GIS approaches emerged that use GIS technology in critical ways. Feminist GIS challenges masculinist assumptions of space and emphasizes embodiment, care, and situated knowledge. Participatory GIS focuses on community-led mapping and empowerment, often in contexts of marginalization. Qualitative GIS explored how narratives, interviews, and emotions could be visualized and spatialized. Other approaches, like Indigenous and decolonial GIS, emphasized sovereignty, place-based knowledge, and resistance to colonial mapping systems.

2.4 Feminist GIS

Kwan, Mei-Po. (2002). “Feminist Visualization: Re-envisioning GIS as a Method in Feminist Geographic Research.” Annals of the AAG, 92(4), 645–661.

Schuurman, Nadine & Pratt, Geraldine. (2002). “Care of the Subject: Feminism and Critiques of GIS.” Gender, Place & Culture, 9(3), 291–299.

2.5 Participatory GIS

Harris, Trevor & Weiner, Daniel. (1998). “Empowerment, Marginalization and ‘Community-integrated GIS.’” Cartography and Geographic Information Systems, 25(2), 67–76.

Elwood, Sarah. (2006). “Negotiating Knowledge Production: The Everyday Inclusions, Exclusions, and Contradictions of Participatory GIS.” The Professional Geographer, 58(2), 197–208.

2.6 Qualitative GIS

Cope, Meghan & Elwood, Sarah. (2009). “Qualitative GIS: A Mixed Methods Approach.” In Qualitative GIS: A Mixed Methods Approach, eds. Cope & Elwood. SAGE Publications.

Pavlovskaya, Marianna. (2006). “Theorizing with GIS: A Tool for Critical Geographies?”

Environment and Planning A, 38(11), 2003–2020.

2.7 Indigenous and Decolonial GIS

Louis, Renee Pualani. (2007). “Can You Hear Us Now? Voices from the Margin: Using Indigenous Methodologies in GIS.” Geographical Research, 45(2), 130–139.

2.8 Affective and Critical Data Studies

Leszczynski, Agnieszka. (2009). “Quantitative Limits to Qualitative Engagements: GIS, Its Critics, and the Philosophical Divide.” The Professional Geographer, 61(3), 350–365.

Wilson, Matt & Graham, Mark. (2013). “Situating Neogeography.” In Critical GIS: Theory and Practice, edited by Schuurman & Wilson, 1–21. Wiley-Blackwell.

2.9 Goals of this Class

My goal is to teach GIS critically in this course. This requires navigating tensions between GIS as a powerful way to analyzing spatial patterns (that is used ubiquitously across public and private sectors) and GIS as a technology that has a history of entrenching institutional power and embedding epistemological assumptions about how we see space. These tensions are especially powerful in pedagogical approaches (the method and practice of teaching).

GIS pedagogy often falls into a problematic binary: critical GIS courses that emphasize reading and discussion about GIS without doing GIS, and technical classes that do GIS without meaningfully engaging in the critiques. This course aims to disrupt that binary. Instead of treating critique and practice as opposites, we will treat them as co-constitutive. As Elwood and Wilson (2017) writes, critical GIS is not just a body of literature, it is a way of doing GIS and as Martin and Wing (2007) argue, instruction can be a site for transformation of GIS. In this course, students will be introduced to the core GIS techniques needed to develop a foundational GIS skillset, while simultaneously interrogating the assumptions embedded in those processes.

Further, in this course, we will practice Open GIS. As discussed earlier in the chapter, the vast majority of GIS courses use proprietary software, engaging with the commercial GIS ecosystem. Free and Open Source alternatives do exist. Open GIS disrupts the representation of GIS as a single inevitable technology. Open GIS is not only a collection of alternative software projects, it is an alternative mode of engaging with GIS, recognizing that GIS software itself is a social artifact. Teaching critical open GIS allows students to become “conflicted insiders”- able to participate in the practice of GIS while meaningfully engaging with the values, assumptions, and power structures embedded in its design and use (Holler (2020)).